One of the greatest problems you’ll face as a formerly incarcerated person is working out how to get your life back on track and avoid the possibility of returning to a correctional facility in the future. Some statistics have shown that without some form of intervention or rehabilitation, most inmates will re-offend within the first 9 years of their release. So, it’s very much in your interest to consider pursuing an education while incarcerated, which will help you to get off on the right foot after your release from a correctional facility.

Table of Contents

One of the best things you can do to improve your chances of succeeding and adjusting to civilian life is to get an education while you’re serving time. In fact, it has been shown that prison education is an effective way to reduce the likelihood of reoffending after release from prison. Unfortunately, you’re going to face some obstacles; access to education opportunities—and particularly to funding—as an incarcerated individual is hard to come by. Options are far more limited when compared to prospective students who haven’t been incarcerated, not only in terms of the choice of courses available but also in terms of gaining access to financial support.

However, if these obstacles can be overcome, then you’ve got a strong chance of drastically improving your prospects by undertaking a course of study while incarcerated. Most importantly, you can significantly reduce the likelihood that you might find yourself returning to prison in the future for subsequent offenses.

Within this article, we’re going to highlight a lot of useful information that will help you to understand what kind of opportunities are available to you as an incarcerated prospective student. We’ll look at what types of funding you can apply for if you need help affording the cost of tuition, as well as some of the best schools and programs you can choose to boost your chances of succeeding with distance learning.

Likelihood of Recidivism

According to the above report from the Bureau of Justice (2018), the recidivism rate—that is, the tendency for a previously convicted criminal to re-offend—stood at 83% for prisoners released in 2005. That’s 5 in 6 former convicted persons being arrested for at least one offense in the nine years following their release, a huge number that clearly shows the risk of inmates becoming trapped in the prison system for life.

But if you take part in prison education, those numbers are significantly reduced. Those who participate in general education and vocational training are much less likely to re-offend and reenter the criminal justice system upon release. What’s more, as an incarcerated person who gained an education while in prison, you’re also likely to be more successful in finding meaningful employment when compared to ex-prisoners who have not had the same kinds of opportunities.

According to the same report, the cost of reincarceration is estimated to be around $8,700 to $9,700 less for those who have undergone correctional education compared to those who did not. And costs associated with providing education to inmates are estimated at around $1,400 to $1,744 per person, showing a clear financial incentive to have more inmates taking up courses while in the justice system.

So, it is one of the most cost-effective means of reforming former prisoners when they leave the justice system. However, there’s further evidence to show that it’s almost one of the most effective outright ways of preventing recidivism too. According to the National Institute of Justice, education in prisons outperforms other means of rehabilitation in reducing recidivism [2]. That includes vocational training, boot camps, and ‘shock’ incarcerations, which are shorter, yet militaristic in style. In fact, in 2001, this was proven by the Correctional Education Association, who ran a study known as the ‘Three State Recidivism Study’ to directly investigate the benefits of correctional education. They proved that long-term recidivism was reduced by 29 percent [3].

Public Attitude Toward Correctional Education

In addition to the already-limiting obstacles around public funding and the difficulties that prisoners face in managing studies alongside their daily obligations, the public attitude toward inmates gaining access to study opportunities doesn’t make matters easier.

A congressional ban on prisoners gaining access to a fund known as the ‘Pell grant’ was put in place in 1994; these funds are granted by the government to low-income students and never have to be repaid. In 2015, the Obama administration moved to give inmates greater access to college-level studies funded by the government. And while the Obama administration couldn’t lift the ban without Congressional approval, the Education Department and the Justice Department were able to run a temporary pilot program, giving Pell grant access to a limited number of inmates.

However, while the administration was fighting for this pilot study, several critics in Congress were already fighting it. A House bill named the ‘Kids Before Cons Act’ sought to bar the pilot from being allowed. For some time, it looked like the ban would remain in place due to opposition against the grants being reinstated for inmates. But fortunately, the opposition didn’t succeed and the Second Chance Pell Pilot Program entered its fourth year in 2019. This initiative offers Pell Grants to students through 64 different colleges and has seen around 1,000 inmates or former inmates graduate with post-secondary or college qualifications since the pilot began in 2016.

Still, the fight that the Obama administration had to go through to have this pilot approved just shows that there is still a negative attitude towards allowing prisoners access to correctional education from the public and some parts of the government. This is just one more obstacle that prisoners face in gaining access to something that could drastically reduce their likelihood of recidivism.

What Does Prison Education Look Like?

The term ‘Prison Education’ doesn’t define any one type of course. This umbrella term can refer to basic numeracy and literacy instruction, or it could include vocational—’on the job’—training that seeks to help inmates gain valuable skills that can be applied to the civilian workforce. It could also include more advanced courses such as full GED or college qualifications.

Most courses are conducted on-site, with trained education professionals delivering courses to groups of inmates at both federal and state correctional facilities. However, some studies can also make use of mailed correspondence. What is harder to find are distance learning courses conducted online due to the restrictions around internet access imposed on inmates at most correctional facilities.

Unfortunately, access to prison education isn’t standardized across the board. The state and correctional facility in which an inmate is incarcerated will largely contribute to the type of opportunities that are available. Factor in the cost of tuition fees and the increasingly sparse public funds allocated to correctional education, and it’s easy to see why access to such courses is limited. Of course, there’s also the time management aspect; whilst studying towards a qualification, inmates are also limited in their rights to free movement and personal time management.

What Types of Education Are Available?

As we’ve already discussed, there are different types and levels of education available to inmates during their incarceration. Basic literacy and numeracy courses are available, which can be a huge benefit to those who have never finished formal education, as these skills are mandatory for even the simplest civilian roles. Inmates may also study towards their GED or even post-secondary, college-level education when made available by their correctional facility. Take a look at the following options that inmates may have at their disposal.

Studying Towards a GED in Prison

For offenders who were incarcerated or involved in trouble from a young age, it’s common to have never finished high school or gained a high school diploma. In fact, previous evidence shows that incarcerated inmates are more than twice as unlikely to have never finished high school. According to a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, around 41% of inmates in state and federal prisons and local jails had not completed high school or its equivalent level of study. By comparison, less than half—18%—of the general population over the age of 18 hadn’t finished the 12th grade.

Lacking a high school diploma or equivalent can be a major impediment to finding employment after release from prison. It’s a basic requirement to gain access to anything beyond the most entry-level jobs in the civilian workforce. However, that doesn’t mean the end of the road for inmates who have never finished high school—instead, they can study for a GED when offered by their correctional facility.

The GED, or General Educational Diploma, is a series of tests that are designed to certify a student’s aptitude, skills, and knowledge. The diploma is only available to those who have never earned a high school diploma, but according to a previous study by the American Council on Education, around 96% of employers in the US will accept a GED as being equal to a high school diploma. Thus, it’s a necessary first step in studying towards higher education such as an associate or bachelor’s degree.

Fortunately, the GED is one of the most commonly offered programs of study available to inmates. This is likely largely due to the fact that the Federal Bureau of Prisons necessitates participation in such programs when inmates do not hold a high school diploma. In most cases, these inmates must take part in basic literacy programs for a minimum of 240 hours or until they obtain a GED. For inmates who do not speak English, there are also mandatory ESL (English as a Second Language) courses that will help them to develop at least a basic level of English, which will further boost the opportunities available to them upon release from prison.

Studying Toward a College Degree in Prison

According to a 2011 report from the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP), in an attempt to further reduce recidivism, policymakers looked at post-secondary correctional education (PSCE). This term covers any vocational or academic study that an inmate undertakes beyond the high school diploma or GED level that can be put toward an associate, bachelor’s, or graduate degree.

The report noted that there is a lack of data available on the level of PSCE attainment within correctional facilities across the country. However, where data is available, those who participated in PSCE saw several positive benefits after their release, including higher educational attainment, reduced recidivism, and better employment opportunities with higher salaries.

The reasons for this lack of data could be attributable to a number of factors. For example, due to the high volume of inmates who have never achieved a high school diploma or equivalent, it’s possible that many are either studying towards basic literacy or numeracy skills or a GED. The lack of access to funding for higher levels of study could also be a contributing factor. While the Pell Grant initiative introduced by the Obama administration helped, it still remains that as of 2018, prison inmates were still in receipt of only 1% of all Pell Grant funding. Clearly, underfunding still remains to be one of the major obstacles standing between incarcerated prisoners and PSCE.

Correspondence Courses

For those who can access PSCE from prison, the list of educational institutions that offer appropriate courses is growing. Most of the programs are delivered via mail correspondence, which is one of the most effective means of delivering such studies to inmates. Study materials for each credit module are delivered to the prison and completed on-site, before being submitted in the same way.

In a recent study, IHEP found that distance learning is the most likely and useful method of study to educate a large population of inmates. Rather than requiring every inmate in a room to study toward the same program, distance learning provides greater opportunities for diversification, meaning inmates can participate in programs relevant to their goals or interests. Thus, this list of universities from thebestschools.org is well-suited to those who want to tailor their studies to a particular course or field:

- Adams State University

- Andrews University

- Ashworth College

- Athabasca University

- Brigham Young University

- California Coast University

- California Miramar University

- Colorado State University

- Colorado State University at Pueblo

- Huntington College of Health Sciences

- Louisiana State University

- Murray State University

- Ohio University

- Oklahoma State University

- Perelandra College

- Rio Salado College

- Sam Houston State University

- Seattle Central Community College

- Southwest University

- Texas State University

- Thomas Edison State

- Thompson Rivers University

- University of Central Arkansas

- University of Idaho

- University of Minnesota

- University of Mississippi

- University of North Carolina

- University of Northern Iowa

- University of Saskatchewan

- University of South Dakota

- University of Wisconsin

- University of Wisconsin-Platteville

- University of Wyoming

- Upper Iowa University

- Wesleyan Center for Prison Education

While it could be due to the limited data available—as mentioned above—the same IHEP report also notes that around three-quarters of prison inmates in education are enrolled in a certificate or vocational courses rather than academic studies. Of the roughly two million incarcerated inmates at the time of the study, only around 71,000 were enrolled in secondary education, and an even smaller subset of those was studying toward an academic degree.

The 5 Best Correspondence Programs for Prisoners

We’re going to finish with a list of the five best prison correspondence programs for prisoners. These are courses offered by some of the best colleges for distance learning, plus they’re all accredited by one of the six regional bodies outlined above.

- Adam’s State University

Adam’s State University runs the Prison College Program, offering print-based correspondence courses to incarcerated inmates. They’re accredited by the Higher Learning Commission—part of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools—and charge just $220 per semester hour. This is less than half the cost per credit hour of some standard degrees and applies to both in-state and out-of-state applicants. Every student will be assigned an advisor who is available year-round via a toll-free telephone line, or through mail correspondence.

As an accredited course provider, Adam’s State University accepts up to 90 credit hours transferred from other regionally-accredited institutions. These can be used toward a Bachelor of Arts or Science degree. Alternatively, up to 45 credit hours can be transferred toward an associate degree. More information for incarcerated students can be downloaded from their website.

- Colorado State University at Pueblo

CSU Pueblo offers distance learning through the Division of Extended Studies. Unlike Adam’s State University, the program isn’t targeted specifically at inmates, but rather “to provide courses to part-time students” from different backgrounds. The university has a good reputation for working closely with incarcerated students. Each week, an ‘Inside-Out’ program has a class meeting with incarcerated women from a local correctional facility, promoting an inclusive syllabus that teaches about issues like crime, justice, and society.

While their degree choice is comparatively limited, their course quality is good; the university is accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. Inmates may take six months to complete a course, which costs around $500.

- Ohio University

The Correctional Education program offered by Ohio University has been offering prison education since 1974, though the courses offered have been trimmed down in more recent years. Incarcerated students can study toward both bachelor’s and associate degrees, but also legal studies certificates. Courses cost approximately $1,000, making them more expensive than some of the other universities we’ve listed, but their long-running history in correctional education is a reassuring quality. The university is also accredited by the same accreditation body as CSU Pueblo and Adam’s State University.

- Texas State University

Texas has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world, which is why the Texas Prison Initiative was founded. Run by volunteers at the University of Texas, the organization offers credit-bearing college courses to incarcerated students at no cost to them. With continued success, there’s also a plan to extend this support to on-site teaching at local correctional facilities.

Otherwise, the university is accredited by the Commission on Colleges and offers correspondence self-paced studies that vary in cost from around $850 to $1,150 for 3 and 4-hour undergraduate courses respectively and around $1,000 for 3-hour graduate courses. However, this program of study is only open to those incarcerated students who are also residents of Texas.

- Upper Iowa University

Much like CSU Pueblo, the distance learning offered by Upper Iowa University is available to both incarcerated and non-incarcerated students who want to study part-time. But like Ohio University, courses are also quite expensive, running at around $1,000 each over six months. Prison life can be tumultuous, so it can be reassuring to know that six-month extensions can be granted if needed.

Accredited by the same regional body as the above universities, they have a larger selection of bachelor and associate degrees available than CSU Pueblo or Ohio State, though not all are suitable for incarcerated students. Courses vary from psychology and business to arts, management, and the social sciences.

On-Site Classes

If you’re not participating in a correspondence course, then your classes will likely take place on-site at your correctional facility instead. This is certainly the case for programs such as basic literacy and numeracy below a sixth-grade level, as well as GED classes for inmates that want to complete a high school-level education. Other courses are often offered too, which usually fall under the broad term of ‘Life Skills’. These may be things such as anger management, how to set and achieve goals, how to develop healthy relationships, and avoiding substance abuse.

Online Study From Prison

As we’ve already mentioned, the already-limited internet access for incarcerated students makes it extremely difficult to offer online study. Technology for online learning is rapidly expanding, yet the risks associated with unrestricted internet access within prisons are too great to utilize all the options available. Though some inmates do have limited internet access via something called the Trust Fund Limited Inmate Computer System, otherwise known as TRULINCS, its reach doesn’t extend to e-learning. While it allows certain inmates a limited level of contact with friends and family outside of the prison, it doesn’t offer much else.

Currently, the use of restricted internet access—under heavy supervision—is approved in 49 different U.S. states, but not in Hawaii, Iowa, Nebraska, and Nevada. These approved states are authorized to offer inmates education programs using online learning, but that doesn’t mean that the practice is widespread. A government report from 2015 highlighted how only 14% of prisons within the U.S. were permitting internet access to inmates, even in its most restricted, supervised form.

In more recent years, some organizations and institutions are beginning to go against the grain. The Eastern New Mexico University (ENMU) has been offering online courses to incarcerated students for around 10 years via their own specialized learning system. Inmates are limited to accessing only this portal and no external website content. Another organization is known as Jail Education Solutions (JES) in the city of Philadelphia ran a pilot program that gave tablet computers to inmates for learning purposes. And finally, a third organization, the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), has begun introducing online courses in juvenile facilities, supervised by a teacher.

Clearly, the attitude towards online education in prisons is changing, but it could take time to become more widespread. In the meantime, there are alternatives—as outlined above—for inmates to pursue an education while incarcerated.

Applying for a Prison Education

If you’ve decided to pursue a prison education, remember that the application process won’t look the same to you as any other unincarcerated student applying in the normal way. So, you’ll need to know what to do when it comes to putting together your application.

- Selecting an institution and course, and applying

Once you’ve narrowed down a list of schools of interest, it’s time to evaluate the courses offered by each institution. While there are many courses that can be pursued under a correspondence program, not all will be accessible to prisoners, meaning there’s a more slimmed-down selection to choose from. Unfortunately, this is again down to the limitations in place for studying inside a correctional facility. For example, this includes courses that require internet access as we’ve discussed, but also those that need a DVD player or other media player. Thankfully, there are many paper-based courses that utilize study guides, textbooks, and written assignments.

- Verifying the college’s accreditation

When you’ve narrowed down a list of potential colleges to study with, you should look at their accreditation status. This is especially important if you’re taking a correspondence course, as there are some non-accredited institutions associated with poor-quality learning and degrees. Colleges offering high-quality correspondence learning will be accredited under one of six accreditation bodies that are backed by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) and the U.S. Department of Education. They are:

- Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools, Commission on Accreditation

- New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Commission on Institutions of Higher Education

- North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, The Higher Learning Commission

- Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities

- Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, Commission on Colleges

- Western Association of Schools and Colleges, Accrediting Commission for Senior Colleges and Universities

While you want your chosen college to be accredited by one of these regional bodies, you should also look for accreditation from the Distance Education Accrediting Commission (DEAC) if you’re taking a correspondence course. This body specializes in distance learning providers, ensuring that accredited schools offer high-quality education. If you choose a college that isn’t accredited by one of the six regional bodies outlined above, then you could encounter problems should you try to transfer any credits gained from one college or university to another.

- Gaining approval from the prison institution

Ensuring that your prison approves your course of study is a simple but essential step. You’ll need to speak to whoever handles education within your prison to make sure that you’re added to the list of approved students. This ensures that you are authorized to receive your distance learning materials in the mail. Usually, the same staff will also act as an invigilator for any exams that you complete on-site, so you should maintain a good relationship with this person, as they will be your primary link to accessing education from prison.

- Enrolling in and completing your course

At this point, your application is complete and your prison has approved you to take part in correspondence learning. You’ll need to order your courses in the mail, which usually involves filling out a form on paper—typically, the college makes the full list available in a prospectus catalog. You’ll also need to either enclose payment for the course in the form of a check or send the forms to a friend or family member to affix payment. When your college has received your order with the payment, the course materials will be sent to you. From here, you can work on completing the required reading, assignments, or examinations.

Financial Aid For Inmates

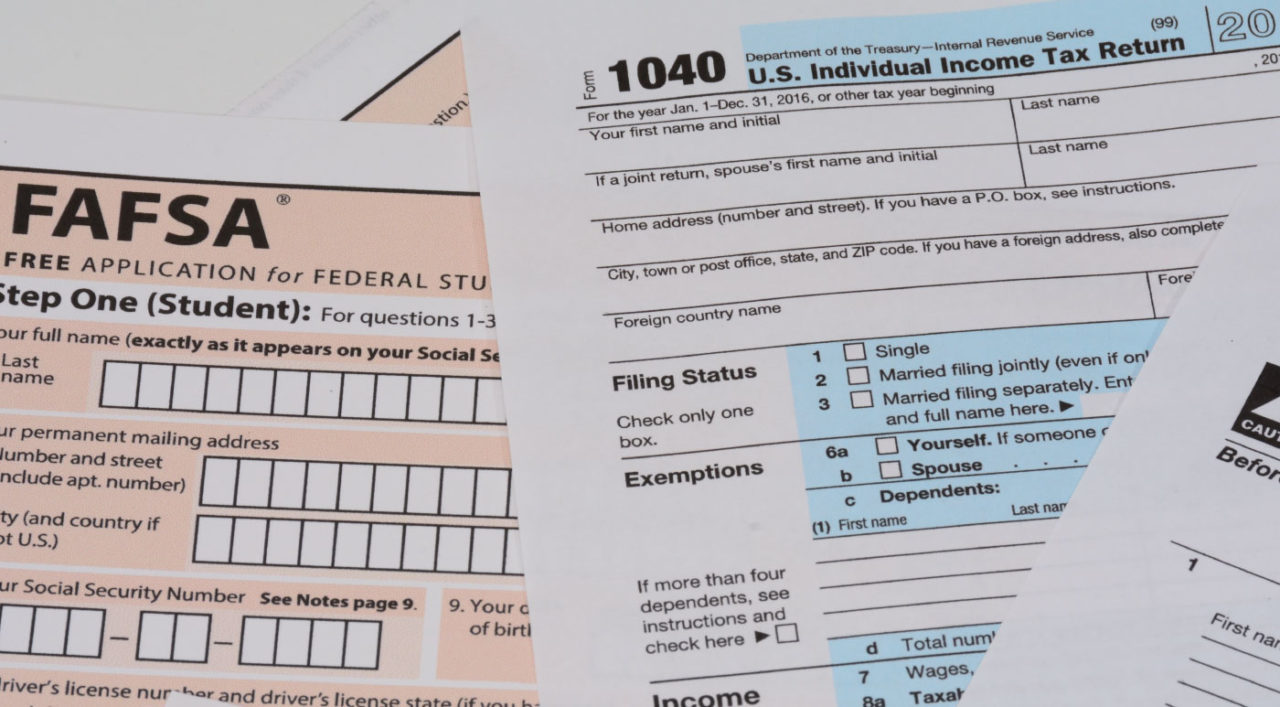

Whether you’re an incarcerated student or not, tuition fees are extremely costly and can be one of the biggest barriers to a college education for any citizen. While some needs-assessed financial aid is available for students who need assistance in accessing higher learning, those with a history of convictions can face even greater difficulty. In some cases, eligibility can be forfeited for ex-offenders. Around 1% of all Pell Grant funding in 2018 went to incarcerated inmates, a minuscule number indeed.

Under the Federal Student Aid Eligibility criteria, there are strict rules around who can and cannot gain access to the various loans and grants made available by the U.S. Department of Education. For certain loans and grants, inmates are automatically disqualified depending upon the institution within which they are serving time. Although there are no disqualifying criteria for certain funding—for example, the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) and Federal Work-Study (FWS)—students who are not incarcerated will be given priority in most cases, which further reduces the likelihood of an inmate gaining funding.

With the exception of some drug-related crimes and crimes of a sexual nature, most eligibility limitations cease to apply once an inmate has been released. However, tackling recidivism is more effective when prison education can take place during the term of an inmate’s incarceration. Even if eligibility criteria looks like a limiting factor, it’s still worth completing a Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, as most educational establishments use this information to grant non-federal funding, because you may still secure another form of funding. Alternatively, you may be selected for a pilot program—such as when the Pell Grant program was established—simply by making your information available.

Scholarships and Grants

Although access to federal financial aid is dependent upon stringent eligibility criteria for inmates, this isn’t the only type of funding available. Groups exist that offer grants and scholarships to those currently serving time, with the goal of helping prisoners to gain qualifications and launch a career after their release. If you’ve been unsuccessful in securing federal funding for education in prison, then you may try one of these organizations.

In 2019, this body awarded the Reentry Project grants—a total commitment of $85.9 million—dedicated to helping individuals return to the labor force from the justice system, and gain meaningful employment. The same grants were available in the several preceding years, with other, similar funding made available through different projects.

The Prison Scholar Fund is a private organization that relies on donations, providing financial aid for limited groups of inmates who can apply directly for funding. If you check out their Success Stories page, you’ll note that many incarcerated and previously incarcerated individuals have been able to turn their life around and begin training towards a meaningful career thanks to funding from The Prison Scholar Fund.

The Prison Education Foundation is another organization relying on funding from donors, which can grant a limited number of scholarships to inmates each year. To quality, applicants need to possess a high school diploma or GED; be a U.S. citizen; have no serious disciplinary incidents in the past year, have no longer than 7 years remaining of their sentence, and be accepted into an associate or bachelor’s degree program approved by the foundation.

You can find some online scholarship listings like this one that may help you to locate other sources of funding that aren’t awarded by the federal government. Again, you should make sure you read any eligibility requirements to see whether you qualify.

Federal Work-Study Funding

In the interest of highlighting all the available options for funding, another means of covering prison education costs is known as ‘Federal Work-Study’. This is not a grant or scholarship; rather, it is paid employment in which a student takes up part-time employment either on or off-campus. However, it’s worth bearing in mind that not every school takes part in the Federal Work-Study Program and those that do participate only have a limited pool of funds to award to students.

It’s likely that formerly incarcerated students who have since been released from prison will have more success finding a place in a Federal Work-Study program. Inmates currently serving time are under strict limitations around movement and freedom, which would make it difficult for them to participate in most jobs under this program. There are fewer off-campus roles available than there are positions on-campus, and of course, prisoners will not be able to work on the college campus while incarcerated.

However, if you do succeed in landing a Federal Work-Study position after finishing your sentence, here are some things you should know about the program:

- Being accepted doesn’t guarantee a position

Even if you’re offered funding under the Federal Work-Study program, you won’t receive the funds until you’ve started earning them. You’ll still need to find a work-study job and while some schools will allocate them out, others require you to find and interview for your own positions much like any regular job.

- Funding is paid like an ordinary paycheck

Whereas other types of funding are often applied directly to the cost of your tuition and school fees, money from work-study funding is paid to you like an ordinary paycheck. Work-study funds are designed to help you manage the costs of living and studying, rather than covering your tuition in its entirety.

- Some jobs are off-campus

You might like the idea of a convenient role that’s close to your residence but bear in mind that not all roles are on-campus. Some might require you to work in a local school or other institution.

- You’re not guaranteed work-study from year to year

From one academic year to the next, there are factors that determine whether you’ll retain your eligibility and funding. These can include your total household income, how you used previously-allocated funding, and how much overall funding the school has available that year.

- Hours and pay can vary

Since work-study roles can vary due to your level of qualifications or responsibilities on the job, the pay can also vary widely too. This may also be affected by the minimum wage set by the state.

Advice for Distance Learning

Distance learning can feel challenging at times, but there’s always support available for students who need it. Above all, you’ll need to remember to be self-motivated and driven; you’ll need to push ahead even when the course becomes challenging. Achieving a degree is a long but rewarding process. Here are our top tips for keeping motivated and ensuring that you make it to the end of your course.

- Be clear on your reasons for studying

Before you get started with your course, think about the reasons you have for doing it in the first place. This will help you when your motivation dips or you encounter challenges. For incarcerated inmates, this might be to avoid reoffending—remember those recidivism studies—or to improve the chances of obtaining work after release.

- Understand your workload

Some courses may provide a calendar that breaks down the required work into a rough guideline of what you should complete each day, week, or month. If the course doesn’t provide it, spend a little time working it out for yourself. If you let work build up then it can quickly become overwhelming, which will only increase the stress and any potential feelings of wanting to throw in the towel.

- Remember to ask for help

Students studying on-campus can easily speak to their professors whenever a lecture ends. For those who are studying online or via correspondence, this lack of face-to-face contact can be jarring. If you become stuck, make sure you ask for help; what this help looks like will depend on whether you’re incarcerated or not. If you’ve been released, consider connecting with coursemates on social media or through your studying portal if you have one. If you’re currently serving time, remember that you’ll have a point of contact—usually your professor—who will help you with any questions you have.

- Organize and back up your work

Even if you’re taking a correspondence course from prison, you’ll want to keep an organized collection of all your materials. In fact, the same applies even after you’ve been released. When it comes time to complete assignments or examinations, the last thing you’ll want is to have misplaced essential documents—especially if you’re incarcerated, where replacements might not be available or could take weeks to arrive.

- Remain positive

We won’t lie and say that it’s going to be an easy ride. There will likely be times when you’ll wonder why you even started the course in the first place. Life inside prison and after release can be challenging and feel like an uphill climb but remember those reasons you laid out at the start of the course. Accept that studying is hard work and persevere.